Art & History:

and why it’s ok to play with Manson Family dolls

(originally published in Guernica)

I have not been good. With the blessing of my life, I have dragged through the disappointments of my millions of mothers and fathers. I have lived, cruel and selfish, upon the labor and suffering of my brothers and sisters. I have hurt those I love. I have wished for the destruction of strangers as casually as I have glanced to the sky. I have learned that even saints are devils, that cognizance itself is hypocrisy, and that we are all liars, all the time. And I have learned, of course, that this isn’t the whole truth.

The stuff of art and intelligence is in the recognition of patterns, the simplification of the divine equation. But oversimplification is banal. That’s the fine line traversed by all art: the simpler the art, the more marketable it is. Simple is easy to categorize, explain to consumers, contour for publicity; conversely, the more complex a work of art, the smaller its audience and the more recondite the conversation around it.

Populist art, streamlined though it is for clarity and distribution, can still attain a “sublime” that would seemingly be exclusive to an art dedicated to what is fathomless. Often with intention, populist art operates on multiple levels, maintaining accessibility in the marketplace while offering other insights or interpretations. Such work comprises much of the classical canon. “The Mona Lisa.” Great Expectations. Ad infinitum. Even unwittingly, as a manifestation of cultural forces, populist art can take on unexpected meaning. Regardless of the lack of forethought, a work of art can be wonderfully enduring. Plan 9 From Outer Space, let’s say, or a Brillo Box from the 1960s. Yet another mode of populist art is collective, achieving nuance and complexity through the contributions of artists and engagement through the ages. The life of Abraham Lincoln, for example, is an ongoing, shared narrative, which we adjust and redirect according to our particular and immediate needs. Sometimes, a story thrives by debate. What was the Vietnam War? Who was President Nixon?

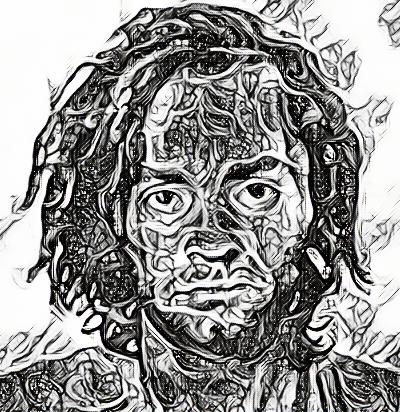

The Manson family is a retelling and a debate. The state-represented story (Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter, presented the prosecution’s argument) and a variety of other accounts serve conflicting conclusions: the racist cult leader, the disappointed musician, the druggie guru, the angry ex-con, the clown, the devil. The narratives of Manson range from engendering hatred to dismissal to sympathy to idolatry. And an ever-burgeoning heap of semi-evidence provides fresh material to aspiring sculptors of story.

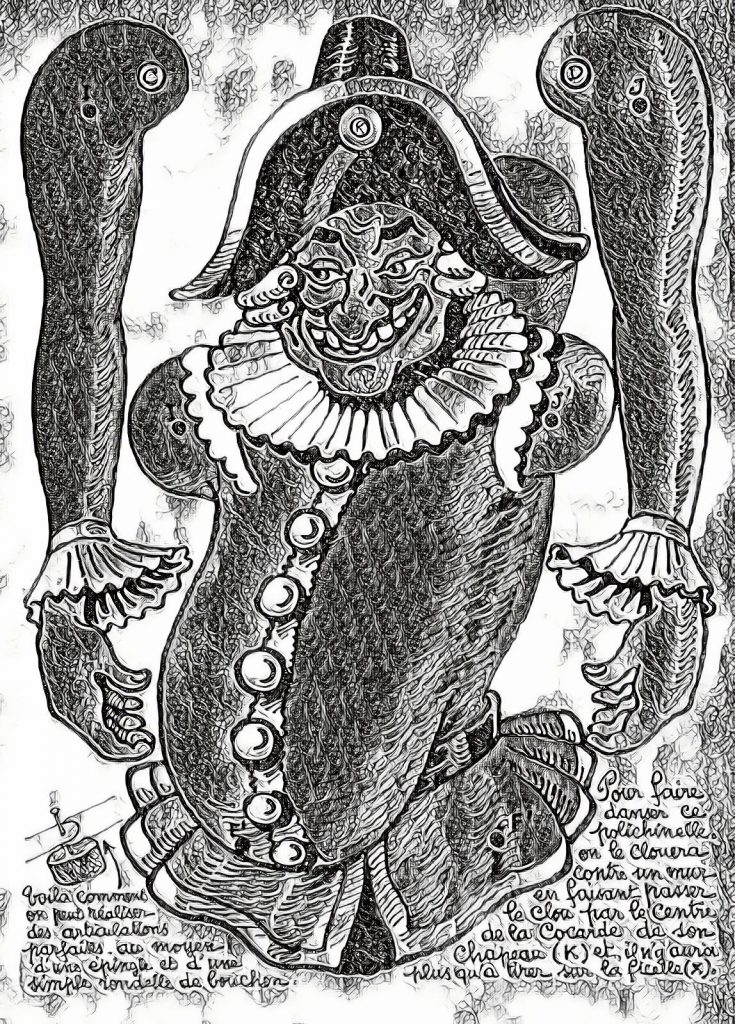

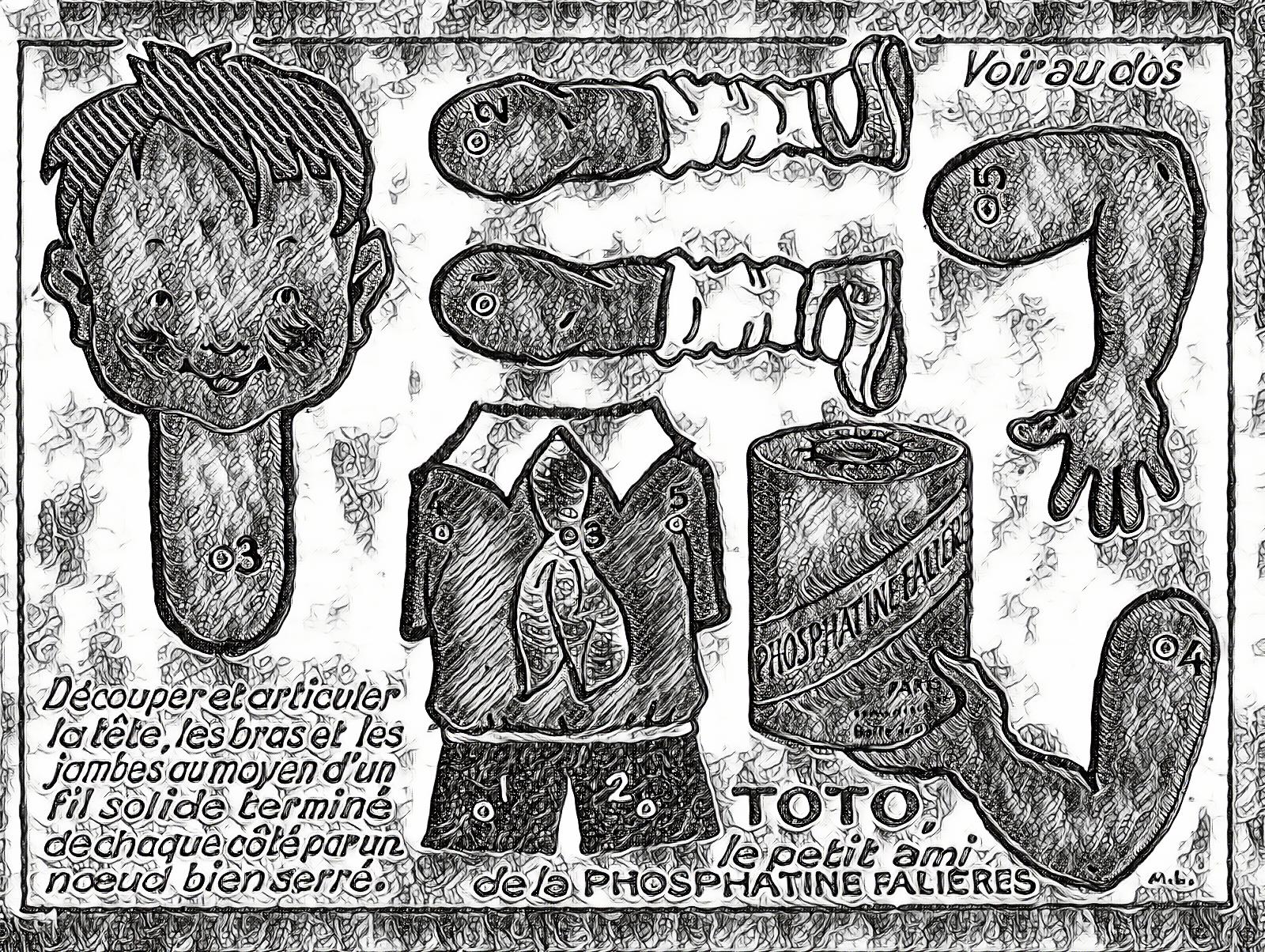

Manson, at a diminutive 5’3″, was always a bit of a human doll; a characteristic he relished. His female followers would dress him–cowboy, biker, Native American–with schoolgirl enthusiasm. That identity is protean is a precept of many, if not all religions–and Manson espoused the mercurial self in a homegrown, prison-philosophy, Haight Ashbury rap. His followers, dressing from a shared wardrobe, also chose identities with frivolous disregard–exercises of pure desire.

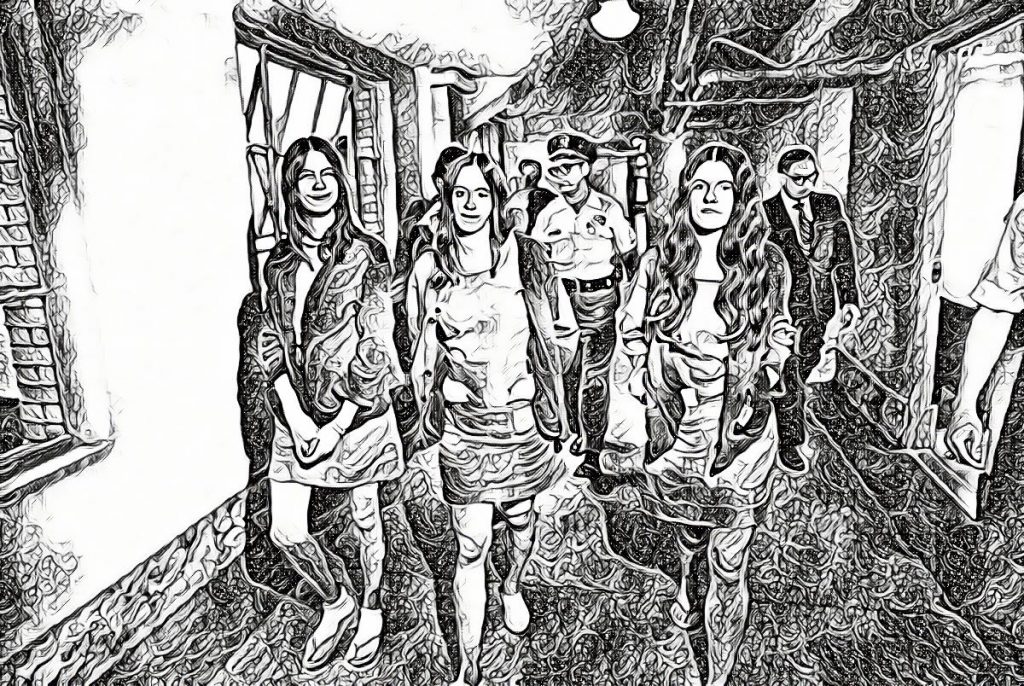

During the trials of Manson, Charlie Watson, Susan Atkins, Leslie Van Houten, and Patricia Krenwinkel, the changeability of the Family was something Manson cited as the source of their sudden popularity. The Family, he said, was a mirror. America would see what it wanted to see: a reason to put an end to the Counterculture; a vindication of the conservative lifestyle; or, a Satanic cult. And in its self-delusion, America would make of the Family what America already was: a society of heartless, murdering hypocrites.

The argument that the Family marked the end of the Sixties is a historical narrative that’s more art than truth. The Family didn’t end the Counterculture; without Vietnam, the unifying dissent of the protest movement was lost, as was a unifying Counterculture agenda. The Family’s defense was yet another spiel; the government, so the contention went, was an organization of killers. True enough, but no defense; governments exist, in large part, to do our killing. If hypocrisy were an adequate defense–that government, being murderous, can’t adjudicate in the trial of murderers–in the course of history, few trials, if any, would have resulted in a finding of guilt.

The US justice system is relatively good at fact-finding, and less so at finding motivations, or accurately assigning culpability, especially in group crimes. The fault extends to humanity in general; not even parents can sort out which of their kids did what for what reason. In the Manson case, the prosecution simultaneously assigned culpability to Manson and to his followers–the trick was mystifying, but closer to the whole truth than a trial could allow. Manson was the leader, but he was also an older, somewhat desperate hanger-on who would do anything to maintain his status. If Bobby Beausoleil was a musician, Charlie had to be more of a musician; if Charles “Tex” Watson started dealing drugs, Manson had to be a bigger, more experienced drug dealer; if Steven “Clem” “Scramblehead” Grogan or Bruce Davis started killing hitchhikers, Manson had to be more of a psychokiller; if Catherine “Gypsy” Share was a radical Armageddonist, Manson had to be more of a radical Armageddonist; if Sandra Good and Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme were Jesus freaks, Manson had to be Jesus; and if Susan “Sadie” Atkins was a Satanist, Charlie was Satan. The members of the Family were Charlie’s sex slaves (Charlie was bisexual, tending homosexual in his attachments), employed to bring Charlie influence over people he judged important, but Charlie, without the cooperation of the Family, was nobody.

The prosecution tells of random criminal insanity, and we look back in cringing horror. But we can’t judge by today’s standards. The revolution was on: this was 1969. Finding an alternative way of thinking/living was a global hysteria. Half a million young Americans were in Vietnam; children torched by napalm were on the nightly news; there were daily protests, bombings, and police actions on campuses; blacks were in a state of uprising, and the pigs were fighting back. Los Angeles, 1969: music, sex, drugs, and more drugs, and the sprawling Cali scene of Manson and his followers. We now suspect that the Manson murders of August 9 and 10 weren’t random: that the political/societal agendas of the crimes were self-justifying, and these were people and houses that Manson and members of the Family knew. The truer inducements for the crime were a snarl of personal envies and criminal avarices.

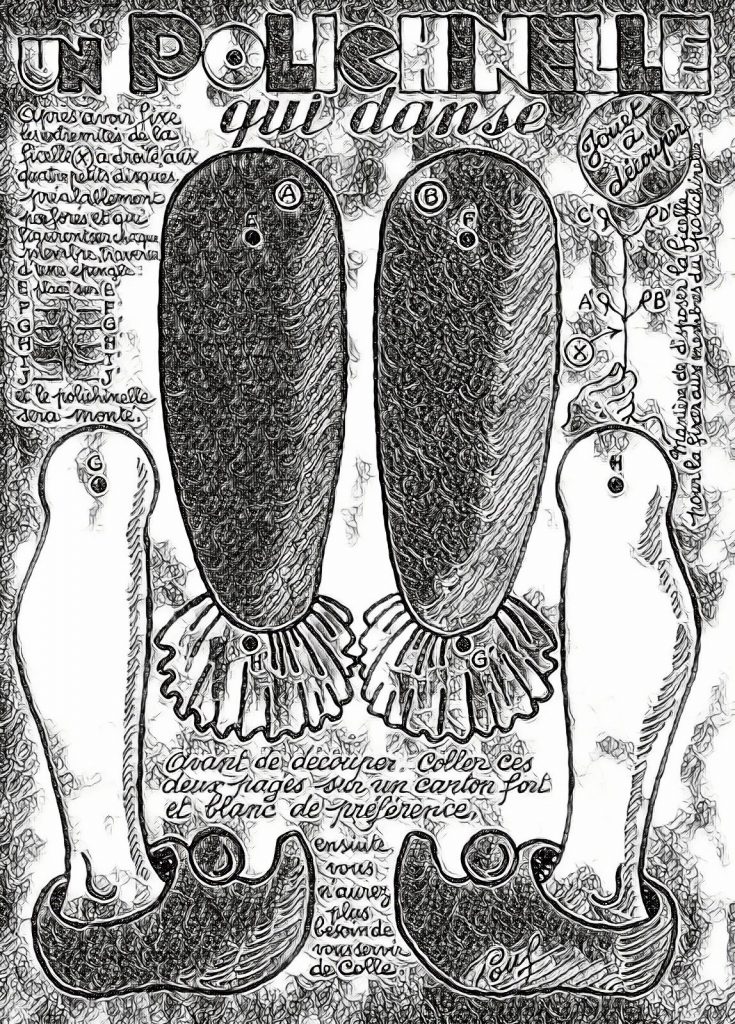

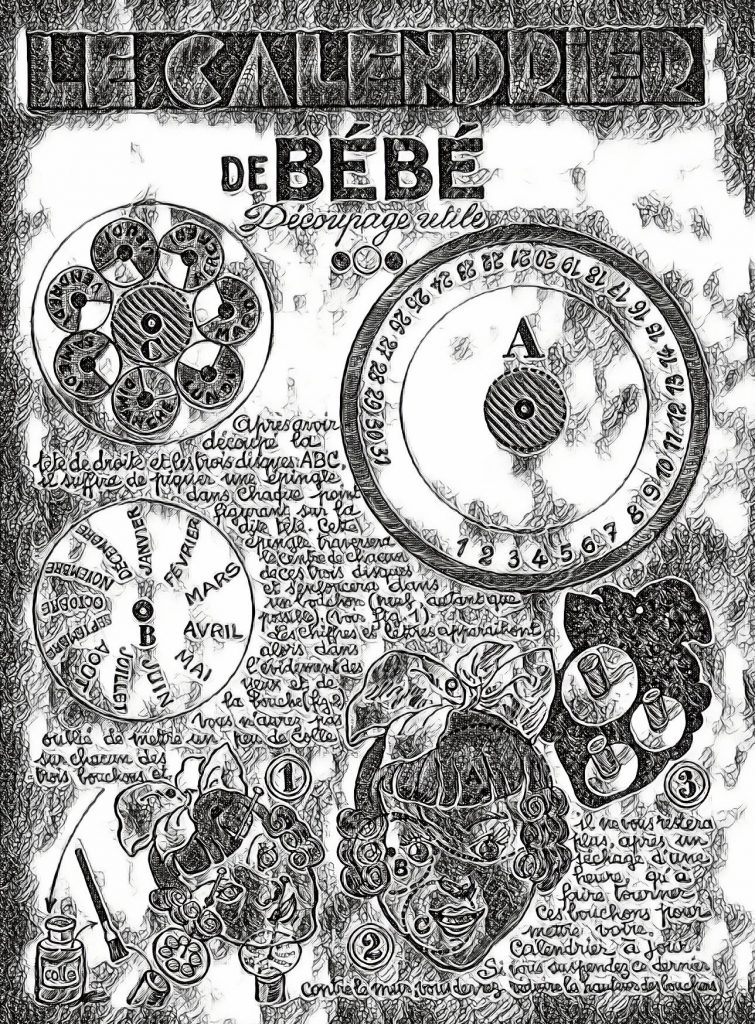

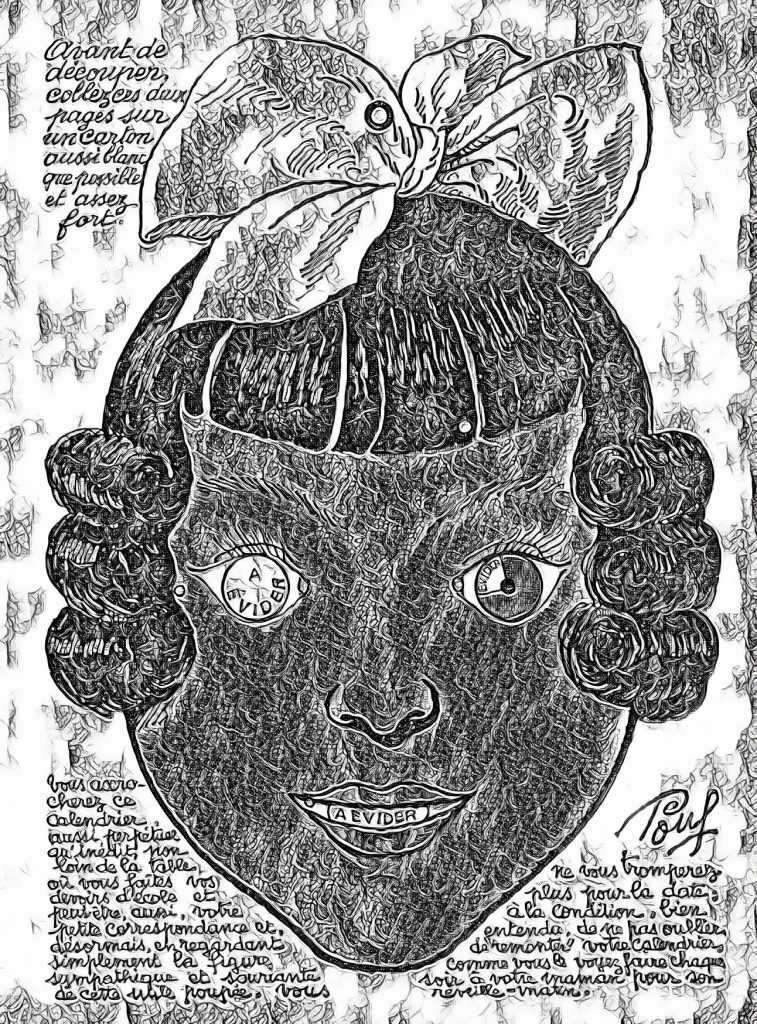

The years since the murders have festered with books, theories, and movies–many of them more right than their predecessors, and many more wrong. It doesn’t help the cause of “truth” that the most authoritative telling, the most “right” telling, is the telling of Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter, which supports his prosecutorial argument. An argument is far from fact, though it may be made up of facts; making an argument, choosing which supporting facts fit how, is necessarily exclusionary. Perhaps due to the conflation of “fact” and “law,” we have failed to piece together a story satisfactory enough that we can set Manson and the Family aside. I’ve endeavored to fall into the category of “more right.” Like those before me, I will have gotten things wrong. This is a book full of names and dates, yes, but more fundamentally, it is a book full of puppets. There is history on the back of every page of paper dolls: to use the dolls, a reader must cut up the history.

As 1968 shifted into 1969, the Manson group was evolving collectively, and each member as an individual. Speed, which Manson didn’t like, had found its way into the chemical mix, and Manson’s followers were deep into their own trips, taking from the costume pile each day, trying on new personas–witches, ranch hands, film stars, drug dealers, whatever. Charlie, to control the situation, enlarged his own presence, and made a conscious effort to diminish their egos. During the court proceedings, the women were the only ones to adhere to their unselves, which, by the time of the killings, were in a continual state of flux. The verdict was a final enactment of patriarchy; Leslie, Pat, and Susan would never get out of jail, while Clem would be paroled in 1985. Bruce Davis was recommended for parole four times by the parole board; like Leslie, who was twice recommended for parole, he was denied parole by the acting California governor. Of the three women imprisoned for the Tate/LaBianca crime, Pat was the most active during the killings. Susan would do a lot of lying and boasting about what she’d done, as would Leslie, to a lesser degree but to more poignant effect. The more you stabbed, she said, “the more fun it was.” Tex, as he has acknowledged, carried out the majority of the killing. Like Sadie and Bruce, Tex rediscovered himself as a born-again Christian; whether to her credit or detriment, Leslie is one of the few ex-Mansonites to have eschewed prison Christianity.

Leslie’s independence–she’s willing to talk about her regrets but hasn’t turned proselytizer–exemplifies what’s interesting about her. Leslie is always at the threshold: she was there for one night of murders, not two; she was the youngest killer (nineteen) and arguably contributed the least; she was the first Family member offered a deal by the prosecution (she turned it down, while Linda Kasabian obliged). And Leslie is still the iconographic Manson killer: the child-pretty, child-talking, ultra-evil brunette. She might one day get parole, but probably not, which is difficult to answer in the context of Clem’s parole; besides being a murderer, Steven “Clem” “Scramblehead” Grogan is a child molester (he was convicted of exposing himself to children) and by the accounts of other family members and associations–unproven, but I credit them–a serial murderer, and a rapist.

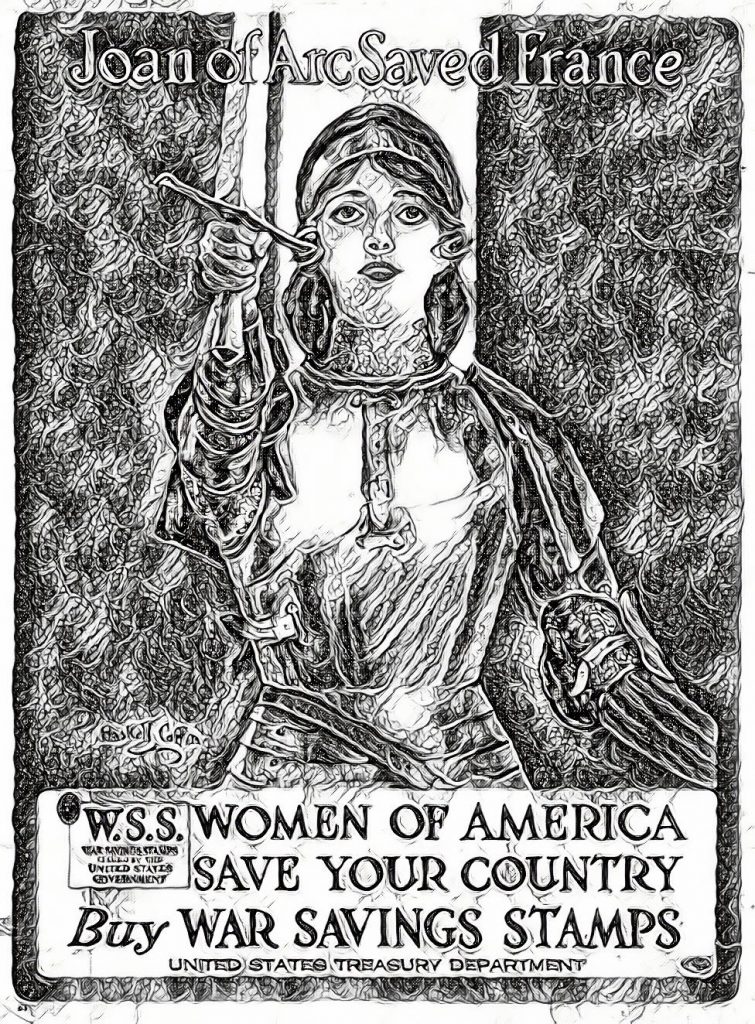

I’m interested in Leslie partly because she resembles people around me, and partly because I’m attracted to who she was, and partly because she fulfills my own (and what I believe to be a national) vision of death, of Athena, of Joan of Arc. In another war, Leslie might have been Joan of Arc–and Charlie, a scrappy Che. It is distasteful to consider such a recasting, or to entertain the villainy of the heroes we do accept. “Justice” is an endless struggle: on the one hand it is the practical dispensation of penalties, on the other, it is the woeful certainty that all crime is a fall of angels–their demises and the repercussions, scaled beyond mortal understanding, of their sins.

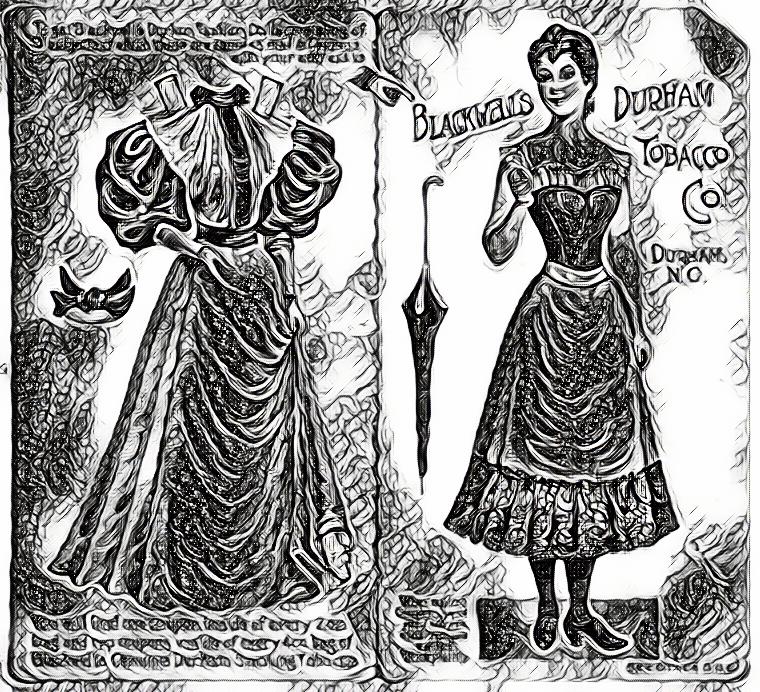

Paper dolls and decoupage are in the midst of an Internet renaissance. Vintage paper dolls, many dating back to the Seventeenth Century, are freely available to print, cut out, and color. The art of the paper doll often bears historic content: this king, or that royal court attire, or in more contemporary incarnations, this wedding dress, or that tennis ensemble. This concurrence of history and paper dolls begs the question: in our storytelling, what is the difference between history and art? The primary distinction would seem to be one of provenance: our historical stories are more collective; our arts (stories, whether in words or other mediums) tend to be more personal. Otherwise, the stories are the same, fashioned from the immeasurable all-nothing, made coherent by their incompleteness, by all that we don’t include.

Regardless of what we’d prefer, history and art are amoral, their truths too large for our monkey measures, their total realities inconsiderate of our ethical comfort. The cutouts of our stories are images of ourselves and our desires; our desires don’t need to make sense. Sometimes our desires are puritanical, or demonic, or hold ethical content, but desire is bereft of morality, as unbound to right and wrong as love.

If the measure of goodness is how we have treated other people, we are none of us good. We are tempters, dissemblers, punishers, and all-too-willing accessories. We have plucked angels from the sky and sometimes we have wept for it, but more often, we have giggled quietly. That is the fear, isn’t it, when we come up with these questionable things? Like a Manson Paper and Play Book! Print and Color Yourself!? That we’re mocking the tragedies of others.

No matter how much we self-censor, no matter how much we insist that there are stories that simply won’t do, that there are stories that we don’t have a right to, that there are stories beneath our dignity–contemptible stories–we understand instinctively, perhaps in our genes, that to deny ourselves stories is to capitulate to stasis. Even the stories that we don’t understand, that we don’t abide, we yearn for. It is that we don’t understand these stories, that we don’t approve of these stories–and yet are drawn to them–that gives the first evidence that our compulsions are essential to us in ways we as yet can’t apprehend.

Are there just two reasons to tell stories? To change who we are, or to stay the same? To seek transformation, or justification? If that’s the case, dubious acts of storytelling–something like, let’s say, a Manson Family paper doll book–have on their side the oratory of radicalism. Change! But if The Family Dolls (color yourself!) isn’t historical compliance, neither is it historical revision. The Family Dolls, to me, is a claim on a story that has gone out of control, that has become a burlesque, a parody, and that has rendered us a helpless, captive audience. Yes, it was my desire to have my very own Leslie Van Houten paper doll book, to be able to dress the Manson Family in stylish ensembles (color yourself!). Don’t you want to, too?

–John Reed, 2015/16